Why 21st Century Investors Should Treat U.S. Equities as the First Choice in Their Portfolios|Invest Where the Giants Swim: Long-Only Capital Leads the Market

Passive Indexing Is the Global Mainstream

From Hedge Funds to Index Giants Asset managers such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street may have roots intertwined with hedge-fund style active management, but today actively managed hedge funds are minority players. They make headlines, yet their footprint in long-term price formation is limited. Far larger—by orders of magnitude—are the faceless, low-cost index buyers that execute predefined mandates month in and month out. Activists are a clear minority; by design, they target underperformers relative to a benchmark and pursue “remedial” alpha.

・Invest Where the Giants Swim: Long-Only Capital Leads the Market

・Global capital loves proven winners—the honor students who have survived the tournament of competition. It is a strategy of betting on the winning horse.

Lower-Performing Strategies Suit GPs with Limited Capital

Real estate, venture capital, and distressed strategies—whose long-run performance often trails the S&P 500 (SPY)—can outperform SPY when the general partner’s (GP’s) own capital base is small and leverage or structure is used judiciously. The point is not absolute return superiority, but that a repeatable strategy creates a GP–LP structure: by accessing other people’s capital at low cost, the GP can still earn attractive economics, including via LBOs, even if the asset class underperforms SPY over time.

・Other than US large equities long-only, the other strategies can be justified only by leverage. Without leverage, it cannot be.

Long-Only Passive Owners Form Stock Prices

For companies that consistently beat their benchmark, share prices are principally driven by long-only passive funds. Vehicles like VTI and SPY automatically accumulate index constituents each month as long as fundamentals do not deteriorate. This is a structural, rules-based bid that compounds over decades.

The Core: Stable Growth in EPS and DPS

Equity appreciation is, in practice, the domain of highly liquid large caps. Prices are formed by long-only asset managers; retail investors have little influence on long-horizon price levels. Critically, equity works best in tandem with financing: secondary offerings, stock options, and bond issuance. Listing only to raise capital once at IPO rarely covers the recurring costs of public-company life (quarterly reporting, annual meetings) unless the firm continues to tap capital markets and reinvest.

Firms that raise capital regularly, deploy it into capex, and grow BPS/EPS/DPS attract long-only flows. In an era when buybacks alone no longer lift BPS structurally, EPS and especially DPS are decisive. Even if BPS and EPS rise, a company that does not grow its dividend struggles to attract durable demand. One-off “special” dividends—e.g., from selling securities or real estate—do not build valuation; only a steadily rising dividend does.

Small Caps Quickly Hit Manipulation Limits: especially in non-US market

In reality, equities are built for large caps that generate—and distribute—cash quarterly. The idea that the next “ten-bagger” must be a small cap is a classic retail bias. Illiquid small caps gap up on relatively small tickets; even buying a few million dollars can lock limit-up and be misconstrued as manipulation. Accumulating several hundred million dollars in sub-$1B names is operationally unrealistic especially in non-US market. Even sub-$10B caps can be awkward: a single $10M print can move prices ~1% in many names. True investability starts above $100B in non-US equities, and even there, many names remain fragile to block flows.

No Block Trades Without Prepared Market Makers

Even mega caps can wobble without adequate market-making. Think of a 5% air-pocket in a $300B name triggered by an abrupt block. If the market-making stack is thin, a ~0.1%–0.2% notional block can still push the book. In many markets, brokers will pre-flag even $10M one-shots in liquid retail staples—because the local infrastructure is not built to digest that flow seamlessly.

The Truth About Price Formation

Strip out short-term noise and equity prices are not about “popularity” or hype. Corporate cross-holdings unwind when sponsors retire; boards eventually sell policy holdings. Over the medium to long run, performance is relative and mechanically anchored to broad benchmarks like the S&P 500.

Why Europe, Japan, and China Underperform the U.S.

Why do U.S. large caps rebound within ~six months of a shock, while markets in faster-growing GDP regions lag? Because of capital-flow architecture. The U.S. dollar commands roughly a third of global currency usage, and U.S. households hold an outsized share of global net worth. Pensions and life insurers worldwide collect payroll contributions and allocate, by mandate, into low-cost U.S. index funds. This creates a circular system: dollars that leave the U.S. economy eventually cycle back into U.S. capital markets.

The Wealth-Circulation Machine: Dollars Leave—and Return

A portion of global payroll, via life insurance and pensions, is continually funneled into U.S. equities. S&P 500 constituents then raise capital at favorable terms, invest in capex, hire at premium wages, and distribute compensation in cash, stock, and retirement benefits—again dollar-denominated—feeding back into Treasuries and equities. Bank deposits and brokerage accounts are likewise dollar-centric; few institutions assume the FX risk of converting dollars to, say, CNY or INR to invest.

Why the Dollar Keeps Winning: Embedded Infrastructure

Market share in commodities trading or cross-border invoicing may fluctuate, but the decisive layer is household finance: salaries, pensions, insurance, and banking denominated in USD. Global trade still prefers USD legs (e.g., JPY→USD→VND) because bilateral currency pools are thin. Card networks (Visa, Mastercard, Amex) settle at global USD scale. The U.S. market thus operates the world’s equity “tournament,” with the S&P 500 as its flagship.

The Most Advanced Governance—and Deterrence

Even if EUR/CNY/JPY gained share, they would still need decades to match the U.S. ecosystem that aggregates world pensions and polices corporate behavior. The U.S. has the broadest base of auditors, lawyers, and tax professionals—and the deepest case law and enforcement history on accounting fraud and shareholder litigation. That legal-infrastructure premium attracts and retains the largest pools of patient capital.

Treasuries and Real Estate Ride on Corporate Earning Power

U.S. Treasuries and U.S. real estate are underpinned by corporate cash-generation capacity. Equity market strength props up both. Hence USD remains the reserve and settlement currency, and U.S. equities remain the world’s largest, most reliable allocation venue—even as emerging markets grow.

The Industrial Base Behind the Market

Layered beneath finance is hard infrastructure: shipping lanes and straits, air hubs, undersea cables, hyperscale data centers, and global military posture. The U.S. also enjoys abundant arable land, energy, and high food self-sufficiency. A large share of marquee hospitality assets is U.S.-backed capital. Consumers may see China or India; owners of the capital base are often American.

What This Means for Individual Investors

A robust default for individuals is to dollar-cost average a fixed share of salary—say, ~10%—into a single low-cost U.S. index (e.g., S&P 500). FX costs and currency swings net out over a decade as the USD ecosystem compounds. This logic holds whether one lives in Japan, Singapore, or Hong Kong.

Prices Are Set by Flows, Not Popularity

Short-term moves are often explained by narratives, but long-term levels reflect net inflows. Index funds, pensions, and insurance are non-discretionary, mechanical buyers that purchase every month. Being included in the S&P 500 is therefore a major demand driver for a company’s shares.

Why the U.S. recovers first after shocks: Because the world’s largest, automatic USD salary-and-pension flows enter U.S. large caps. Market makers are deepest where those flows concentrate. High GDP growth outside the U.S. does not translate into equity strength without a mature, permanent inflow mechanism and the legal/market plumbing to support it.

Why Japan trades as an S&P dependent variable: Foreign investors—often ~70% of turnover—benchmark to the S&P 500 or MSCI World. When S&P rallies, surplus capital spills into Japan; when S&P sells off, Japan follows. Liquidity and market-cap depth are smaller, and few listings deliver sustained EPS/DPS growth at block-trade scale.

Why U.S. Equities and the Dollar Look Like a “Perpetual Machine”

- Pension & Insurance Flows: Global payroll contributions stream into U.S. markets.

- Corporate Flywheel: Raise → Invest → Hire at high wages → Compensation cycles back into markets.

- Currency Hegemony: Salaries, pensions, insurance, and deposits are USD-denominated.

- Institutional Bedrock: Auditors, lawyers, regulators, and disclosure norms at unmatched scale.

- Infrastructure & Security: Logistics, digital backbones, and defense that protect capital.

- Industrial/Resource Base: Scale in agriculture, energy, and manufacturing across a continental market.

Emerging markets struggle to catch up because equity strength requires permanent flows, enforceable investor protections, deep professional talent, and market-making capacity—not just GDP growth.

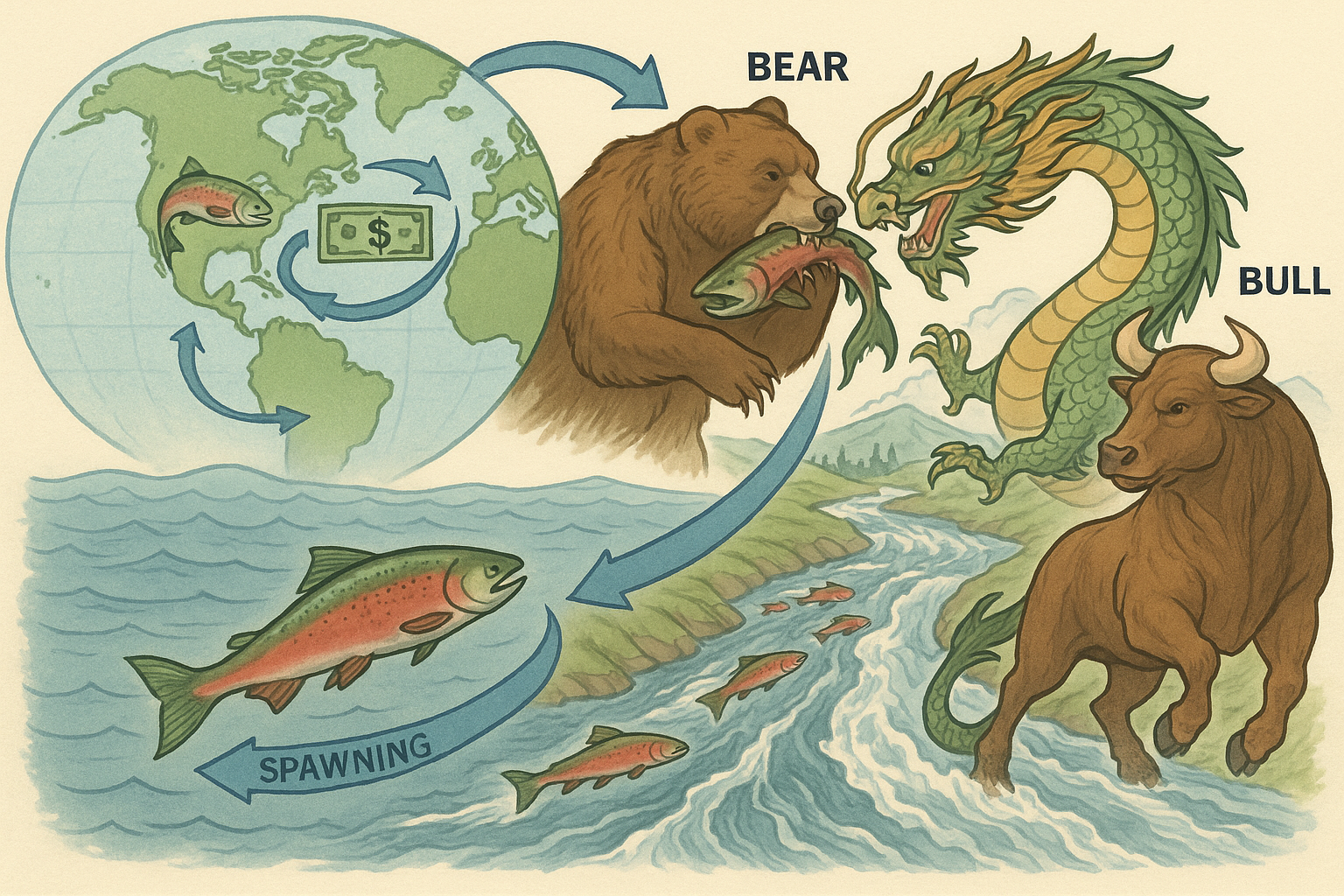

The Flow of the Dollar and the Metaphor of Salmon Migration

Salmon are born in rivers, journey out to the sea, and spend many years roaming the world’s oceans as they grow. When they reach maturity, salmon return to the very river where they were born, swim upstream to spawn, and ultimately die after leaving behind new life.

In much the same way, U.S. dollars are issued in America and circulate around the world through international trade, resource transactions, investment, and tourism. Eventually, those dollars flow back home in the form of investments in U.S. stocks, Treasury bonds, real estate, or payments for imports and capital inflows.

This cycle—where “the dollar travels the world and returns to America to generate new capital”—parallels the life cycle of salmon in Hokkaido: born in rivers, nurtured in the sea, and returning upstream to leave behind the next generation. As the bear seizes the salmon—the dollar returning home—the struggle itself becomes the turning point that transforms into a bull market. As the grizzly seizes the salmon, the salmon transforms into a dragon—and from the dragon emerges the bull.

Bottom Line for Individuals

One of the simplest optimal policies: allocate part of each paycheck to a low-cost S&P 500 index on a dollar-cost-averaging schedule. FX noise is transient; the USD-flow engine is structural.

In One Page

- Prices follow flows, not popularity or GDP.

- Even EPS growth is not a sufficient condition without inclusion in the flow machine.

- The U.S. uniquely combines corporate earning power, labor absorption, USD pensions/insurance, securitized real estate markets, legal infrastructure, and national security—an integrated stack no other region currently matches.

- Consequently, U.S. equities rebound fastest, and the dollar remains the anchor currency.

- History cycles—17th-century Netherlands, 18th-century France, 19th-century Britain—but the 20th and 21st centuries are, for now, United States.

If aliens were to come to Earth, the first place they would go would probably be the New York Stock Exchange. If they were trying to efficiently collect Earth’s currency, they would first look at the American market. Even if you start a startup in Japan, 40% of your assets and sales will likely be American, and if you’re not heading in that direction, you’re doing something unnatural.

From a planetary vantage point, rational capital starts at the New York exchanges. Even a Japan-based startup will likely see ~40% of asset and revenue gravity toward the U.S. over time; resisting that pull is fighting first principles.

Of course, the first choice for a portfolio was the Netherlands in the 17th century, France in the 18th century, and Britain in the 19th century. From the conditions of the 20th and 21st centuries, it follows that today the United States holds that position.